Forgive me for going back in time briefly with this post to the Friday before the last event I discussed, to discuss Kalpa, the exquisite performance constructed by Hirokazu Kosaka at the Getty Museum. The night was cold but the buzz of the first grand performance marking the kick-off of the Pacific Standard Time Performance and Public Art Festival was enough to keep the large (and growing) crowd in good spirits (never mind the addition of some after hours libations!). As people mingled and meandered around the large open entrance courtyard two parts of the performance were immediately noticed, the glaring spotlight directed upward to the cloudy sky above Los Angeles and the eerie spring-like sounds seeming to emanate from the central trees in the space. Like clockwork, at 7pm sharp I noticed the last tram descend the hill and realized that in the fluorescent glow of the compartments stood figures dressed all in white and that a crowd had begun to amass around the platform.

I quickly cut through the crowds to see the beginning of the performance before most of the thousand-or-so spectators had even realized the show had begun and was delighted to have a clear view of Butoh choreographer Oguri laying still on the cold marble clutching his legs in a fetal ball. He slowly began to move, impossibly slow his movements were  considered and delicate. He emerged and entranced us all with his meditative balance and control but by this point the crowd had realized (whether through twitter or in-person buzz) that there was something to see and I was quickly shoved out of the way as people jostled for position. Between Oguri’s movements through the crowd, his spot-light holder, and the licensed photographers and videographers for the event, we spectators began a unique dance of our own, scurrying out of the way while maintaining visual contact and attempting to hold our relative positions to the assembly. The spotlight highlighted Oguri’s movements and bounced off his loose white clothes combating the glow in the crowd of a thousand glowing screens and flashes.

considered and delicate. He emerged and entranced us all with his meditative balance and control but by this point the crowd had realized (whether through twitter or in-person buzz) that there was something to see and I was quickly shoved out of the way as people jostled for position. Between Oguri’s movements through the crowd, his spot-light holder, and the licensed photographers and videographers for the event, we spectators began a unique dance of our own, scurrying out of the way while maintaining visual contact and attempting to hold our relative positions to the assembly. The spotlight highlighted Oguri’s movements and bounced off his loose white clothes combating the glow in the crowd of a thousand glowing screens and flashes.

The dancer began his movement around the courtyard and was soon joined by four additional similarly-dressed performers who made their way to the far wall only to be completely engulfed by the crowds. Soon the dancers fell one by one back across the court toward the ascending stairs, their movements intertwined and inward at times and at times aggressive and outward, attempting to cut through the crowds in their quest. At the beginning of the performance guards attempted to lead the crowds to one part of the courtyard, clearing out this central space, but those of us who followed the direction w here immediately replaced in our earlier positions by the masses that continued to arrive, so I think they gave up the attempt. So, I’m not sure whether it was Kosaka’s intention to have the performers completely surrounded by spectators or whether the original concept would have kept distance and space. These choices certainly affect the reading of the movements, I must admit.

here immediately replaced in our earlier positions by the masses that continued to arrive, so I think they gave up the attempt. So, I’m not sure whether it was Kosaka’s intention to have the performers completely surrounded by spectators or whether the original concept would have kept distance and space. These choices certainly affect the reading of the movements, I must admit.

As the dancers began to emerge from the crowd and make their way up the Getty’s shallow steps, we could see more clearly their interactions and peaceful concentration. As the spotlight illuminated the grand stairway and upper platform, a grid of 400 spools of colored thread came into view. Soon, the performers had placed threads in each of their mouths and synchronously began to descend the steep central passage trailing the gracefully draping thread through sculptures and finally over and through the assembled crowd. We stood mesmerized by the play of light and shadow through the thread overhead as well as the staunch expressions on the

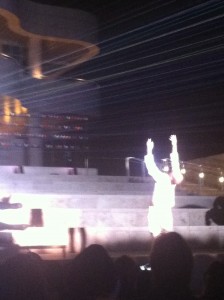

spools of colored thread came into view. Soon, the performers had placed threads in each of their mouths and synchronously began to descend the steep central passage trailing the gracefully draping thread through sculptures and finally over and through the assembled crowd. We stood mesmerized by the play of light and shadow through the thread overhead as well as the staunch expressions on the  performer’s contorted faces as they struggled to drag the threads hundreds of yards using only their mouths. Once the thread had cast a beautiful net over the entire performance space, Oguri once again took center stage, standing outside of the crowd and below the thread, holding his bent arms up to the sky as if in petulant prayer, his illuminated body a question mark to the heavens as fibers from the thread above floated quietly through the air. The massive audience was still for just a moment before the flashes and movement began again, or maybe the stillness was just in my mind.

performer’s contorted faces as they struggled to drag the threads hundreds of yards using only their mouths. Once the thread had cast a beautiful net over the entire performance space, Oguri once again took center stage, standing outside of the crowd and below the thread, holding his bent arms up to the sky as if in petulant prayer, his illuminated body a question mark to the heavens as fibers from the thread above floated quietly through the air. The massive audience was still for just a moment before the flashes and movement began again, or maybe the stillness was just in my mind.

Kosaka’s Kalpa fits squarely into the Pacific Standard Time initiative. The artist was educated at the renown Chouianard Art Institute in the 1970s and worked in Los Angeles throughout the essential PST period, and the performer, Oguri, a transplant to LA, incorporates so much of Los Angeles’ performance history into his work today. These kinds of collaborations and inspirations are where PST functions best, to show how LA art has changed the greater trajectory of art history. This collaboration between Kosaka, Oguri, and the aural sculptor, Yuval Ron, to create a work inspired by sources as wide-ranging as the performance legacy of Ruppersberg and Burden, the spiritual traditions of Buddhism and Hinduism, and the artistic innovations of the Gutai group and Butoh dance, represents what Los Angeles art does best, innovation based on evolution. Artists take bits and pieces, materials and ideas, and bring them together to create something completely novel.

Kosaka’s Kalpa fits squarely into the Pacific Standard Time initiative. The artist was educated at the renown Chouianard Art Institute in the 1970s and worked in Los Angeles throughout the essential PST period, and the performer, Oguri, a transplant to LA, incorporates so much of Los Angeles’ performance history into his work today. These kinds of collaborations and inspirations are where PST functions best, to show how LA art has changed the greater trajectory of art history. This collaboration between Kosaka, Oguri, and the aural sculptor, Yuval Ron, to create a work inspired by sources as wide-ranging as the performance legacy of Ruppersberg and Burden, the spiritual traditions of Buddhism and Hinduism, and the artistic innovations of the Gutai group and Butoh dance, represents what Los Angeles art does best, innovation based on evolution. Artists take bits and pieces, materials and ideas, and bring them together to create something completely novel.

The definition of Kalpa used by Kosaka in Hindi means something akin to aeon, a measure of long expanses of time. Another definition however, is as ritual, one of the disciplines of Vedanga Hinduism. I think really both are applicable to this performance. Kosaka, a Buddhist priest, also engages imagery from his own tradition, he says, ““It is believed in the Buddhist faith that once every hundred years, an angel comes down from heaven and swipes the surface of a stone with her silk sleeves until the rock disappears. This idea comes into play in my performance, as it demonstrates the deliberate, unseen passage of time, and the tangible objects that we use to measure it.” The idea of measuring time is one familiar in art and religion, and lends itself to representation in literary and visual forms, such as the oft-depicted Moirai (Fates) of Greek mythology. These three female figures, Clotho who spun the thread of life from her spindle, Lachesis who measured the allotments, and Atropos who cut the thread of life, are frequently mentioned in poetry and visually conjured by sculptors and painters. In Kosaka’s case, his measurements are made by the performers themselves, winding and pulling the thread of life through their own great efforts. Ayu-Kalpa is the term used within Hinduism for the life expectancy of a human, said to correspond to the virtue of the people during that time period. This performance seems to place that determination squarely on the back of the people themselves, they establish virtue through determination, strength, and will.

Perhaps that is not it at all, and instead the thread wipes clean the modern era, we fall below the new surface, encapsulated as something new begins. Our own time is instead the soil that will fertilize what comes next, a beauty can be found in the end as well as the beginning. This idea resonates with the works Kosaka cites as formative. In an interview with Glenn Phillips from June of 2010, the artist talks about his introduction to the idea of performance, “I think when I came to Chouinard, Allan Kaprow’s book on Happenings had already been printed. There were Gutai photographs in that book. That was very surprising. The word “Happening” was a kind of fashion for that period, not so much the word “performance.” I don’t think Gutai group called them happenings or performances. The word Gutai means concrete forms. That’s what’s Mr. [Jiro] Yoshihara, the leader of the group, was concentrating on. He painted circles all his life. The circle connotes Zen ensō, meaning empty. I think that’s the word Gutai was trying to say something about, this Buddhist notion of emptiness. I don’t think Allan Kaprow knew that. I talked to him a couple of times about that, and he just said, “I don’t understand.” But John Cage was profoundly moved by ensō. He did a lot of pieces about that.” The Gutai group that was so important to Kosaka’s early period as an artist emphasizes the idea of material and destruction, allowing the material itself the freedom to express its reality without bowing to the soul and that expression often is clearest upon the disintegration of its man-made form. In their manifesto they write, “The novel beauty to be found in works of art and architecture ofhte past which have changed their appearance due to the damage of time or destruction by disasters… This is described as the beauty of decay, but is it not perhaps that beauty which material assumes when it is freed from artificial make-up and reveals its original characteristics?” Although not a part of Gutai, Kosaka is clearly considering these concepts in his work. In another part of the manifesto they state their mission, “We have decided to pursue the possibilities of pure and creative ability with the characteristics of the material in order to concretize the abstract space.” In this way Oguri and Kosaka take over the space of the museum, the space of the spectator, and allow the material to float over us, to take on and yet rise above the symbolism so entrenched in our psyche to become material once again. Part of their ability to do this comes from the use of Butoh which itself began as an intervention in the established form of Japanese contemporary dance.

Butoh began around the time of Gutai’s establishment and Kosaka’s own beginning, after World War II. The dance is mostly defined by what it is not, what it breaks away from, from the contemporary dance tradition that relied on western forms mixed with traditional Japanese theater like Noh. Tatsumi Hijikata, said to have performed the first butoh piece, utilized notions of the grotesque, of darkness and decay, similar to the elements of material that preoccupies the Gutai group. These connections were explored more deeply in the 2007 Getty exhibition, Art, Anti-Art, Non-Art: Experimentations in the Public Sphere in Postwar Japan, 1950-1970.

Oguri says about Butoh, “Today the world is top-heavy with information. Humans are losing instinct and are like domestic animals without masters. Dance is the only way to restore the senses to a body in crisis.” By incorporating a dance that restores the senses to the body, and a visual tradition that restores the authenticity to the material, the performance, Kalpa, was able to restore a sense of presence to the spectator.

This video shows the dancers preparing for the performance, and how it might have looked without the crowds.